Ultimate Guide to LLM Memory

How do you add memory to your agent or LLM? What works and what does not? How do you use multiple memory systems at once to cover each others weaknesses?

Most LLM memory systems make your product worse.

Engineers add them expecting a database. Instead they get something slow, expensive, and unreliable. Mention memory tools to anyone running agents in production and you get the same reaction: “It’s heavy.” “The latency kills us.” “Great in theory.”

The problem isn’t the tools. It’s that there is no universal LLM memory. The industry uses several methods to fake it, and each solves a different problem. Pick the wrong one and you pay for capability you don’t need while missing what you do.

This guide covers the patterns, how to match them to your use case, and how to swap them out when something better drops.

Memory ≠ Database

Before we get into the details, we need to change your mental model about what “memory” means in the world of AI and LLMs.

Most of us adding memory to agents aren’t LLM experts. We build something with an LLM and want it to remember things between sessions. We search online, find some cool “memory system”, slap it on top, only to discover it makes our product slow and confusing. And it barely remembers anything useful.

When we think of memory in software, we think about databases: we “store things somewhere” and “fetch them later”. Modern databases are robust and deterministic. Fifty years of software engineering has gone into making sure they don’t fail in production. Databases were built to store and retrieve data for which you knew the exact shape, the exact constraints, and wrote the code yourself. They are deterministic by design.

LLMs operate under different constraints than the code you manually write to call a database:

Humans are unpredictable. LLMs are unpredictable. You’re interfacing between two unpredictable systems in a protocol that allows virtually anything (text).

- The type of data you deal with is “random text that contains useful stuff”, but you rarely know what’s useful up-front.

- You have an upper limit on the amount of data you can include and shove into an LLM until it becomes slow, costly, and inaccurate (confused).

- LLMs are by their very nature non-deterministic. Same input can yield different results.

Every memory system is picking a point on this trade-off triangle:

These constraints mean you need to work around the non-determinism, the limitations of the LLM, and the nature of the input data.

Say you’re building a voice assistant for a hospital and want to store useful data for diagnostics. You cannot do so deterministically. Imagine if you saved data every time a user mentioned “feeling unwell”. You’d quickly find your entire database filled with useless data from patients discussing other people rather than themselves because they’re lonely.

Unpredictable systems are like async/await. Once you introduce it, you can’t escape it. You can only build around it. Memory systems are inherently unpredictable because of the environment they’re deployed and built within. Databases are predictable by design. They are not the same.

What Is “LLM Memory”?

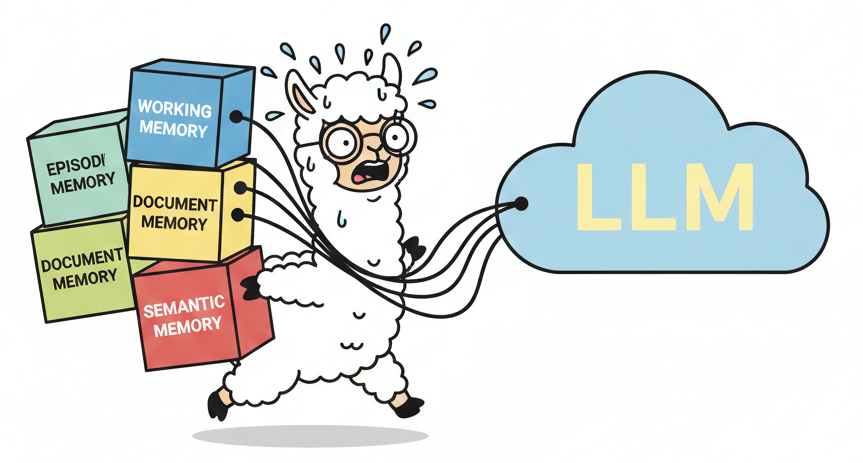

Because LLMs and humans are both unpredictable, the industry is building memory in layers: working memory, episodic memory, semantic memory, and document memory. Each serves a different purpose and solves a different problem.

A useful mental model:

- Working: what I’m thinking right now

- Episodic: what I experienced (concrete events)

- Semantic: what I know (facts from experience)

- Document: what I can look up (external reference)

Working Memory

Working memory keeps the LLM on track with what it’s currently doing. Think of it like a scratch pad the LLM needs to update continuously to track what it’s doing, what it has tried, and what it’s trying to achieve.

Working memory is usually localized to the immediate context of the LLM and is never truncated or messed with. Simple versions include keeping the last 100 messages, storing data in a file and updating continuously, or maintaining a todo list.

LLMs usually take multiple turns to complete a task (making them agents), yet they’re stateless. Working memory helps them continue with a task they started in a previous turn.

LLMs have amnesia (much like Dory in Finding Nemo) and write things down in their working memory to remember next time. It’s the log of what they’re thinking about, what they’re planning to do, etc.

Working memory is a “structured context window” for your LLM.

Episodic Memory

Working memory tracks what’s happening now. But what about yesterday? Last week? Episodic memory gives your LLM a timeline of past events it can reference.

Think of it as a structured history log. What happened, when, and in what order. “Last Tuesday you asked me to draft that email.” “Earlier in this conversation you mentioned your deadline.” Episodic memory makes these references possible.

Episodic memory works on selective inclusion: you decide what events to remember, how to log them, what details matter. An additional agent or LLM typically handles extraction, deciding what’s worth persisting for future reference.

Episodic memory is usually called “summarization”, and you may see that term used instead. It’s a technique for how to achieve episodic memory in its most simple form, where you “summarise” past messages into a log of useful episodic events. Read more about it here.

Semantic Memory

Users interacting across multiple sessions often feed the same data repeatedly into the LLM’s episodic and working memory. If I’m diabetic, I probably have to tell the LLM that every session. How else would it know?

Semantic memory extracts important facts from episodic and working memory and persists them for future sessions. It’s a way to remember user preferences and personalize experiences. Read more about it here.

Semantic memory, like episodic memory, works on selective inclusion. You use another LLM or agent to extract entities, facts, and relationships. Whatever is interesting to remember. These are then selectively persisted for future turns or sessions.

Document Memory

Working, episodic, and semantic memory deal with information from the conversation or the user. Document memory is different: It’s reference material. Your knowledge base, your docs, your internal wikis.

The industry calls this RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation). You store documents in a searchable index, usually as vector embeddings. When the user sends a message, you search for relevant chunks and inject them into the prompt before calling the LLM. The LLM doesn’t know this information and doesn’t look it up. You do, and you enrich the prompt with what you find.

Say you’re building a customer support bot. The LLM has no idea what your pricing tiers are or how your refund policy works. You index your help docs. When a user asks “how do I get a refund?”, you retrieve the relevant policy and hand it to the LLM. Now it can answer accurately.

When to Use What

Memory is additive. You start with one layer, need more capability, add another. Each layer solves a different problem. Each can be swapped independently as better solutions emerge.

Most apps start with working memory alone. You add layers as you need new capabilities:

| You want to… | Add… | Now you can… |

|---|---|---|

| Have multi-turn conversations | Working | Track what’s happening right now |

| Reference things from earlier | + Episodic | “You mentioned this earlier” works |

| Remember users across sessions | + Semantic | Personalize without re-explaining |

| Answer from your own docs | + Document | Cite internal knowledge accurately |

This is a progression, not a menu. You stack layers. A production chat assistant might use all four: working memory for the current turn, episodic summaries for older context, semantic facts for personalization, and document retrieval for domain knowledge.

You can also stack multiples of the same type. Two document stores: one for user uploads, one for your knowledge base. Two episodic memories: one for the current session, one for cross-session history. The layers compose however your use case demands.

Autonomous agents typically need all four, each tuned differently. Working memory tracks execution state: what step am I on, what have I tried, what’s next. Episodic memory logs what the agent learned across tasks. Semantic memory stores extracted facts about the environment and user. Document memory provides reference material for decision-making. Agents are more demanding than chat assistants because they execute multi-step plans where each layer plays a distinct role.

Latency and Cost

Every layer adds latency and cost. Working memory scales with context length. Episodic and semantic memory add LLM calls for summarization and extraction. Document memory adds vector search plus the tokens you inject.

We benchmarked this elsewhere. The tradeoffs are real. A voice assistant can’t wait two seconds for semantic memory extraction. A batch agent processing documents overnight doesn’t care.

Failure Semantics

Remember: LLMs and humans are both unpredictable. Your memory system will fail. The question isn’t if, it’s how. We’ve written about this elsewhere, but here’s the short version:

| Layer | When it fails… | Product impact |

|---|---|---|

| Working | The LLM forgets what it’s doing mid-task. | Task fails. User starts over. |

| Episodic | “We discussed this earlier” stops working. | User notices, re-explains. |

| Semantic | The LLM forgets who you are between sessions. | Minor friction. User re-explains. |

| Document | The LLM hallucinates instead of citing your docs. | User gets wrong answer. Trust erodes. |

Not all failures are equal. Semantic and episodic failures degrade the experience. Users notice, get annoyed, re-explain themselves. Frustrating, but recoverable.

Working and document failures are different. A task that fails midway wastes user time. A hallucinated answer damages trust, or worse, causes real harm. For these layers, it’s better to error explicitly than to silently produce garbage. If your document retrieval returns nothing relevant, say so. If working memory is corrupted, stop the task. Crashing beats confident hallucination.

Common Mistakes

These patterns hurt more products than they help:

Using the wrong layer for execution state. Tools like Mem0 and Zep are built for personalization. They extract facts, build user profiles, remember preferences. Great for “remember I prefer dark mode”. Catastrophic for “remember what step I’m on in this 12-step deployment”. If your agent loses track mid-task, you’re using the wrong memory type.

Adopting a generic “memory solution”. Off-the-shelf memory tools make decisions for you. What to remember, what to forget, how to retrieve. These decisions should be yours. Your chat assistant and your autonomous agent have different needs. A tool that works for one will produce weird failures in the other.

Adding layers before you need them. Working memory is powerful on its own. Modern context windows are large, and your LLM can do a lot with just a well-structured prompt. Start there. Add episodic when users need to reference past conversations. Add semantic when personalization matters. Add document when you have a knowledge base worth querying. Each layer adds complexity. Earn that complexity by needing the capability.

Forgetting that layers are swappable. The point of composability isn’t architectural elegance. It’s survival. The best summarization technique today won’t be the best in six months. The RAG approach you choose now will be obsolete. Build so you can rip out any layer and replace it without rewriting everything else.

How to Add Memory

Memory systems aren’t mutually exclusive. You compose them.

A chat assistant might need all four types working together:

- System prompt + last 100 messages (working)

- Summary of older conversation (episodic)

- Extracted user facts (semantic)

- RAG results from your knowledge base (document)

The trap is reaching for an off-the-shelf solution that promises to handle “memory” generically. These produce weird failures because they make decisions for you that should be yours to make.

The better approach: treat your prompt like code. Each memory type is a component. Components can be swapped, removed, or upgraded independently. When a better summarization technique drops, you swap that piece. When your needs change, you rip out what you don’t need. Your prompt structure stays stable while the pieces evolve.

The examples below use Cria, a prompt composition library I built for exactly this problem. The concepts apply regardless of what tools you use.

Prompt Layout

Every piece of memory you pull in competes for space. System instructions, retrieved documents, conversation summaries, user facts, recent messages, the current query. They all need to fit. When you query an LLM, you’re assembling a prompt from these pieces. The layout matters.

LLMs weigh information two ways, and understanding both shapes how you structure prompts.

By position. LLMs focus on the beginning and end of a prompt. Middle sections fade into background noise. Place stable context (system instructions, user facts) early. Place dynamic context (recent messages, the current query) at the end where it captures attention.

By proportion. Whichever memory type dominates your prompt gets more of the model’s focus. The needle-in-a-haystack problem works in reverse: a bloated haystack doesn’t just hide needles, it captures attention that should go elsewhere. Pull in 1000 RAG chunks and the model drowns in them, even if five matter. Keep each memory system constrained so none overwhelms the rest.

Think of your prompt as a layout with a fixed ceiling. Each model has a context window, a hard upper limit on tokens. You know this number for whatever model you use. But filling to the edge is a mistake. Performance degrades well before you hit the limit, sometimes dramatically. The goal is maximizing useful content while staying comfortably below the threshold where quality drops.

Assign each memory system a region. RAG results might get 2000 tokens. Conversation summaries get 1000. User facts get 500. Recent messages get 1500. These numbers are illustrative. Your actual budgets depend on your model’s context window and your use case. The point is giving each memory type a ceiling. System instructions and the current query are sacred, always included. These constraints keep one memory type from eating the haystack.

cria

.prompt()

// working memory: what are we doing?

.system(instructions)

// document memory

.vectorSearch({ store, query, limit: 5 })

// semantic memory in another store (tech is used across memory types)

.vectorSearch({ store: factStore, query, limit: 15 })

// episodic memory

.summary(messages, { id: "conversation-summary", store: summaryStore })

// working memory: the last messages for relevance

// which also captures tool calls

.last(messages, { n: 100 });Composing for Different Use Cases

Different applications need different memory compositions. A chat assistant, an autonomous agent, and a support bot all use the same building blocks but weight them differently.

Chat assistant: Personalization matters. Semantic memory (user facts) and episodic memory (conversation summaries) take up most of the layout. Document memory is secondary. You might not need RAG at all if the assistant is general-purpose.

cria

.prompt()

.system(assistantInstructions)

// semantic memory dominates

.assistant(userFacts)

.summary(messages, { id: "assistant-summary", store })

// working memory

.last(messages, { n: 20 });Autonomous agent: Execution state is critical. Working memory dominates. The agent needs to track what step it’s on, what it’s tried, what failed. Episodic memory logs task history for learning. Document memory provides reference material for decisions.

cria

.prompt()

.system(agentInstructions)

// working memory dominates

.assistant(currentPlan)

.assistant(executionLog)

// document memory for reference

.vectorSearch({ store: knowledgeBase, query: currentTask, limit: 5 })

// need more messages in working memory to

// do longer running work continuously

.last(messages, { n: 200 });Support bot: Document memory dominates. The bot needs to cite your help docs, knowledge base, product information. Semantic memory (customer info) helps personalize. Episodic memory matters less since support conversations are usually single-session.

cria

.prompt()

.system(supportInstructions)

// document memory dominates

.vectorSearch({ store: helpDocs, query: customerQuestion, limit: 10 })

// semantic memory for personalization

.assistant(customerRecord)

// working memory, don't need that many messages since it's likely

// to be multiple sessions over time that episodic memory captures

.last(messages, { n: 25 });The composition pattern stays the same. What changes is which layers you include and how much of the layout you give them.

Handling Conflicts

Memory layers contradict each other. Your semantic memory says “user prefers dark mode”. Your episodic summary says “user switched to light mode yesterday”. What wins?

LLMs handle this well if you capture when something was true. “Preferred dark mode (January 2024)” vs “switched to light mode (December 2025)” gives the model enough to reason about recency. Make sure your memory system records timestamps.

Off-the-shelf tools like Zep and Mem0 handle reconciliation automatically, using an LLM to merge or update facts as they come in. If your use case depends on facts staying accurate over time, pick a memory system that supports this.

Vector search is trickier. RAG can fill your budget with contradictory facts, and you can’t tell which are current. Episodic memory helps because it preserves temporal order. A summary beats a bag of conflicting chunks.

A Complete Example

Here’s a chat assistant with all four memory types, priority-based fitting, and swappable stores:

const summaryStore = new PostgresStore({ tableName: "summaries" });

const vectorStore = new QdrantStore({

client: qdrantClient,

collectionName: "knowledge",

embed: embedFunction,

});

const prompt = cria

.prompt()

.system("You are a helpful assistant.")

// Document memory: RAG results

.vectorSearch({

store: vectorStore,

query: userMessage,

limit: 5,

priority: 2 /* we can live without them */,

})

// Episodic memory: auto-updating summary

.summary(conversation, { id: "conversation-summary", store: summaryStore, priority: 1 })

// Semantic memory: user facts

.omit(

cria.prompt().assistant(await fetchUserFacts(userId)),

{ priority: 2 /* we can live without them */, id: "user-facts" }

)

// Working memory: recent messages

.last(conversation, { n: 200 });

const messages = await prompt.render({

provider: openai,

// cap at 100k because we see accuracy decrease beyond that

budget: 100_000,

});This example uses Cria, a prompt composition library we’ve been building. If we hit the budget, Cria shrinks what we can live without (semantic and document memory) while keeping the rest intact.

The pattern matters more than the tool. Structure your prompts so you can adapt as the space evolves.

What About Research on Memory for LLMs?

The future looks promising. Real breakthroughs are happening. At some point “LLM + memory” will become a non-issue. We won’t get there without stepwise improvements in LLM infrastructure, but we’re moving in the right direction.

The pattern worth watching: systems we build around the LLM are slowly getting absorbed into the LLM. This is good news. It means we can pick winning patterns now, knowing the best ones will eventually become native capabilities.

As of early 2026, here’s how recent developments map to the four layers:

- DeepSeek Engram: a conditional memory module that adds constant-time (O(1)) lookup into massive N-gram embedding tables, fused into the model via gating. Deterministic addressing enables prefetch and host-memory offload with minimal inference overhead. This is document memory baked into the model. Similar in spirit to vector search, but without the retrieval latency.

- Recursive Language Models (RLMs): an inference harness that treats long prompts as external environment state (e.g., a Python REPL variable), letting the model inspect it in code and recursively call itself over snippets. This extends working memory. The agent harnesses we build today, formalized as an inference pattern.

- Claude chat search and memory: Claude can search past conversations across sessions and maintain memory summaries across chats and projects. This is episodic and semantic memory as a product feature. Simple, but often wins in real workflows because it works.

These aren’t true memory yet. They don’t give LLMs the kind of episodic recall or semantic persistence we’ve described as fully general capabilities. But they’re absorbing specific layers: Engram eliminates document retrieval latency. RLMs formalize working memory patterns. Claude’s memory handles episodic and semantic for consumer use cases. The layers we build today are scaffolding. Some will become unnecessary as models absorb them. Others will evolve into something better.

The goal isn’t finding the perfect memory system. It’s building something you can evolve.

This space moves fast. The state of the art today won’t be state of the art in three months. Whatever you build needs to adapt, or you’ll be ripping it out and starting over.

That’s the real argument for composability. Don’t settle for whatever’s kinda working today. Build a structure where you can swap out any layer when something better drops. Add capabilities when you actually need them. Evolve with the space instead of getting locked into last month’s best practice.

We’re building Cria to ensure you can swap out whatever you need in the future. If you’re solving similar problems, check it out.